Jonathan Franzen is a notable novelist, naturalist, and journalist, so his recent critique in the New Yorker ("Carbon Capture," 4/6/15), not just of the Climate Change movement but of a whole world-view associated with it, deserves some critical attention. In brief, Franzen tells us to avert our gaze from the dismal future, appreciate what's in front of us here, now, and try to preserve what we can of our natural world--even if the whole shebang is going to blow before century's end. His message is therapeutic in a way, but is it responsible, or even tenable?

He begins with a particular gripe: after the National Audubon Society declared climate change to be the "greatest threat" to bird species in this century, a blogger on bird-related issues for the Minneapolis Star Tribune drew the false inference that lesser (but quite real) concerns like the reflective glass in a newly built stadium that kills thousands of birds no longer really matter--mean "nothing," as he crudely put it. Of course it's perfectly reasonable to believe that both the short-term and the long-term dangers matter, the dead birds today, the dislocated species tomorrow, both signaling our need to get involved.

But Franzen prefers to see this story as a parable of something larger. Drawing on the work of philosopher Dale Jamieson (Reason in a Dark Time) he examines the ethical implications of what he (following Jamieson) considers a hopeless, desperate eschatology: climate change has already happened, it will inevitably get worse, nothing can plausibly arrest it. This being the case, our only ethical choice is to adjust to living within its new paradigm. Birds will: unlike the Audubon Society, Franzen believes the adaptability of birds will serve them in their new environments, and he paints a surprisingly sanguine picture of how bird species in a warmer North America "may well become more diverse."

In any case it doesn't matter because we are doomed: following Jamieson, Franzen notes how poorly adapted the human brain is to considering longer term matters such as the survival of one's grandchildren, how vast and intangible the climate and energy questions are, how little any of us can do, given our "0.0000001 per-cent contribution" to emissions. Democracy is a system for marshaling only the most nakedly short-term self-interest of voters, and anyhow, a modest middle-class American life-style already produces way more CO2 than is tolerable as a global average. "Replacing your incandescent lightbulbs," as the Audubon folks helpfully suggest, just won't do it--though Franzen fails to even consider how using fossil-free renewable energy to generate electricity renders the type of light bulb irrelevant, and and how full-scale energy conversion would permit middle-class America to persist in its affluence without climate-based destruction.

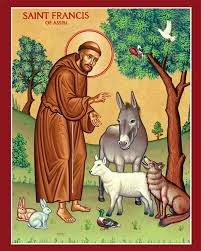

Indeed, Franzen prefers to think that no aspect of the problem--"global governance, market failure, technological challenge, social justice"--can be successfully addressed. He sets aside some notionally contestable factors--for example, that"fossil-fuel corporations sponsor denialists and buy elections"--as somehow beside the point, and the possibility of collective action--of the 350.org sort, for example--seems not to occur to this writer, absorbed as he is in the dilemmas of the atomized homeowner and citizen. Why are such potential solutions not worth considering? Because, as Franzen hastens to observe, we are in the grip of something too big to fight, namely Protestant Guilt. We need global warming, we need to believe we have irrevocably polluted our Eden, because it confirms our sinfulness, and brings on the punishment we deserve. What can we do instead? Embrace the alternative, Franciscan vision: "helping something you love, something right in front of you."

Franzen goes on to describe some remarkable projects that do just that: projects in habitat reclamation, the creation of sustainable agriculture to compete with slash-and-burn rainforest exploitation, the loving care of 'wildness' wherever it has been preserved. Does it make sense to engage in such environmental restoration when the whole global environment is poised on the brink of climatic changes such as it perhaps hasn't seen for eons? Franzen, unlike the scientists and policy makers desperately trying to achieve international consensus at the Paris conference, accepts those changes as a "done deal," and yet he insists that the work of environmental restoration must go forward. What else can we do? I admire both his pursuit as a journalist of these stories, hidden away in the Amazon lowlands or the Costa Rican forest, and even more so I admire the perseverance of the indigenous peoples, scientists, and NGO staffers who are doing what they can. Preserving what one can of biodiversity, reversing human despoliation, these are useful for the earth and for our souls. But isn't the attempt to limit the extent of climate change useful too, even if it may be too little too late? Are we so sure it's a 'done deal'?

I feel a bond of sympathy with Franzen's anger, his impatience with simplistic nostrums, his attraction for the real work of dedicated ecologists in the field, whether indigenous farmers or university researchers. But I am distressed that he is ready to concede the larger climate issue, and consign our efforts to the ephemeral sphere, token acts of kindness while waiting for the end. We need both sorts of intervention, all at once, local conservation and global energy conversion, now, tomorrow, for as long as it takes. I haven't read Jamieson's ethical treatise yet, but I am ready to insist that calling ours a "dark time" will not by itself shed more light.

No comments:

Post a Comment